Vicente Ogo, who has been raising and fighting roosters since he was a child, sold all of his birds during the past year because of a new federal cockfighting ban for the U.S. territories. It takes effect Dec. 20.

Ogo, 38, of Maina, Guam, said some local cockfighters have been skeptical about the ban and its impact on the sport, but he takes it seriously and doesn’t want to jeopardize his federal job, working on a military base.

Ogo on Saturday evening competed in one of the last legal cockfights on island and in the nation, at the Dededo Game Club. He “sponsored” a friend’s roosters in the three-cock derby format, paying half of the total $2,500 competitor fee. That’s an entry fee of $1,000 per contestant and a mandatory minimum bet of $500 per fight.

With nearly 60 competitors at the event, the main prize was more than $50,000, awarded to the contestant or contestants with the most wins. Bet callers, who work for tips, used hand signals to take side bets from spectators before each fight.

“It’s pretty sad,” Ogo said of the federal ban. “I love breeding chickens and fighting them. I grew up with it.” He said the sport is misinterpreted and he doesn’t believe it is cruel. He loves animals and owns five dogs, who live in his home, he said.

MORE:Cockfighting ban is an issue of political status, says Independent Guåhan

A doctor for the birds

As Ogo spoke in a staging area behind the spectator stands of the open-air warehouse, bird doctor Marlon Pareja, 55, worked quickly to sew a cut on Ogo’s sponsored rooster. The bird won its fight — the first victory of the night for Ogo and his partner — but it had a cut on its leg from the razor strapped to the losing bird’s leg.

It was a busy night for Pareja, who gets $20 per bird, live or die. About halfway into the evening’s event, Pareja had worked on five birds, with three more in their wooden carrying crates waiting to be strapped down with cords and sewn up.

Pareja sprayed each closed cut with oxytetracycline, an antibiotic in a small bottle he got from the Philippines.

Pareja, who works as a courier, said he makes more money working at cockfights than at his day job. The extra money helps pay for his son’s tuition, he said.

“I don’t know what will happen” when the ban takes effect, Pareja said.

Ogo said, over the years, he fought his birds at the Dededo cockpit, at village fiestas and at backyard cockpits, sometimes for medical fundraisers. For fundraisers, $50 of the $250 entry fee for contestants goes toward medical care, he said.

Ogo said he wouldn’t be surprised if residents continue to cockfight after Dec. 20, taking the sport underground.

He’s done, he said.

“I don’t want to get in trouble.”

Federal cockfighting ban

The federal law that expands the existing national cockfighting ban to Guam and the other U.S. territories takes effect Friday, one year after President Trump signed the measure into law.

Under the ban, those who sponsor or exhibit birds in a cockfight face a fine and a maximum prison term of five years if convicted. Attending a cockfight would be punishable by a fine and as long as one year in federal prison.

The sport has been federally banned because of animal cruelty, but local government leaders have defended the practice and have promised to push for its legalization. Congressional delegates from the other U.S. territories also have opposed the ban.

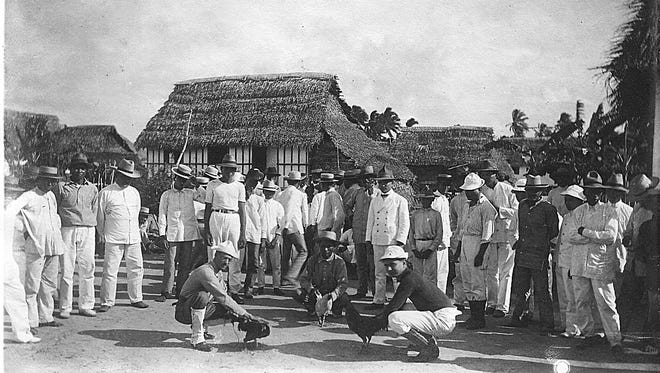

Gov. Lou Leon Guerrero has said she will do “whatever is necessary” to restore cockfighting, which she said has a historical significance on Guam. It is believed cockfighting started on Guam sometime during the early 1800s, under the Spanish government, brought to the island by Filipino immigrants.

“It may not be an indigenous culture and was brought over by the Spaniards, but it was brought into the CHamoru traditions and practices,” she said.

In the meantime, residents need to follow the law, the governor said this week, even if it’s an unpopular law.

Del. Mike San Nicolas in August told local lawmakers the federal ban “supersedes and invalidates” all local laws that conflict with the ban. That means all Guam laws that legalize, regulate and tax cockfighting will be void, beginning Dec. 20.

“Unfortunately, the supremacy clause of the United States Constitution prohibits any past or future legislation the Guam Legislature enacted regarding the issuance or maintenance of licenses for cockfighting in Guam,” San Nicolas wrote, adding he is trying to get a cockfighting exemption for the U.S. territories through a separate bill.

Enforcing ban is ‘lowest priority’

Unable to change the federal ban, the Guam Legislature included a provision in this year’s budget bill, stating enforcing the ban “shall be the lowest priority of the government of Guam.”

The Office of the Attorney General last week noted cockfighting isn’t illegal under local law, so there is no action it can take, other than to notify federal authorities.

“Because there is no local basis for criminal action, if the (Office of the Attorney General) receives any criminal complaints it will be forwarded to federal law enforcement authorities,” the attorney general’s office stated.

Gov. Leon Guerrero said cockfighting doesn’t harm the community and therefore should be a low priority for local law enforcement.

To ensure the federal ban is enforced on Guam, the Animal Wellness and Foundation and Animal Wellness Action last week announced it will pay a $2,500 reward for any information that leads to a federal cockfighting conviction.

A group of former attorneys generals from the mainland issued a statement this week, urging political leaders in the territories to make it clear to the animal fighting community that they must follow the law or risk going to prison.

“Give me a break,” responded Guam Speaker Tina Muna Barnes. “In the case of cockfighting, nobody sought the input of the people of Guam when they decided to craft legislation that would impact our local residents. Now a bunch of former attorney(s) general from other states are telling me that they know more about our island and our culture?”

Big bets on fights

About 200 people attended Saturday’s derby. The last derby at the Dededo facility was scheduled for the evening of Dec. 19, a two-cock derby with a $500 entry fee and a minimum bet of $200 per fight.

The amount of money wagered, won and lost at a cockfight can be significant — six figures, in some cases.

Roberto “Bec-Bec” Malig, who operates many of the fights at the Dededo facility, said the cockpit’s Thanksgiving derby drew more than 100 contestants, each of whom paid an entry fee of $2,500, plus a $500 minimum bet for each of the six fights.

Like many cockfighters, Malig said he was introduced to the sport as a child and he started cockfighting on Guam when he moved here from the Philippines in 1994. Working at the Dededo Game Club has been his primary occupation for the past decade, he said.

The cockpit will comply with the ban and stop operating, said Frank Charfauros, son of cockpit owner Edward T. Charfauros.

“After this, no more job,” Malig said.

Ponz Manalo, who helped Malig weigh-in and tag roosters Saturday morning before the derby, said he thinks the federal ban is disgusting.

“Everybody has a different opinion,” he said, when asked if cockfighting is cruel. Bet callers and others who earn extra money from the sport will lose out, he said.

The fights at Saturday’s derby happened every 10 minutes of so, allowing for the roosters to be displayed by their handlers and for side bets to be placed. An announcer called for birds paired up for upcoming fights to be re-weighed and ready.

Roosters attack each other quickly and aggressively, and with a long knife strapped to the back of their left leg, most fights ended in less than a minute after one bird stopped moving. A referee lifted and dropped each bird to demonstrate to the crowd whether it could still move or had been killed or incapacitated.

Economic impact beyond the cockpit

The banned sport’s economic impact extends beyond the cockpit.

Rick Davo, 79, owner of Agat’s Pacific Gamefowl Supply, has been selling chicken feed and equipment to support cockfighting in the same location since 1974, a small wood-and-tin warehouse on Route 12, across from Pop’s Bakeshop.

In addition to selling to cockfighters, who represent about 90 percent of his business, Davo and his grandson, John Santos, 26, are active in the sport. They last competed during the Agat Mango Festival in May. They keep about 60 roosters in cages on the grounds of their business.

This is the time of year when cockfighting normally ramps up, they said, because the painful molting season has ended and roosters are sporting fresh feathers.

MORE:Cockfighting enthusiast challenges federal animal fighting ban

As Davo spoke last week, several different customers drove up to the warehouse to buy chicken feed. A 45-pound bag, costing $25, is enough to feed 12 roosters for a month, Davo said.

Davo and Santos last week showed off a couple of their prize roosters: a Kelso Roundhead that won three different times at the Merizo fiesta; and an Albany that is a four-time winner at derbies in Dededo and Merizo.

“This chicken fights very smart,” and is very alert, Davo said of the Kelso. “Once he catches you, that’s it.”

Santos said choosing which birds to fight in a derby involves many factors, including the bird’s demeanor, its appearance and its eating habits. “It’s hard to explain. You just know,” he said.

“To stop the cockfighting, I don’t think it’s right,” said Davo, who became involved in the sport as a child in the Philippines, and who fought chickens in Texas when the sport still was legal there before he opened up shop on Guam.

“It’s the recreation of the older people. It’s just a hobby,” said Davo, who said the sport is more heavily practiced in Guam’s southern villages, something he attributed to influence from the large number of Philippine immigrants who settled there.

Davos questioned who will enforce the ban and how, but said he is concerned he will lose business if longtime customers give up the sport for fear of being arrested.

“It’s gonna hurt,” Santos said of the ban, because some of the people currently involved in the sport won’t want to risk losing their freedom.

Local cockfighting licensing

The government of Guam’s licensing and regulatory infrastructure for cockfighting started to wind down since the ban was signed into law last year. The one-year terms of the most recent members of the Cockpit License Board expired in May, and the governor hasn’t nominated a new board.

The Dededo Game Club is the island’s last and only licensed cockpit, although its five-year license technically expired in 2005, according to records at the Department of Revenue and Taxation.

Cockpit board member Anthony Lujan, owner of Big Ben & Company, never has attended a cockfight and said he knows little about the sport and its terminology. Lujan said he was surprised then-Gov. Eddie Calvo nominated him to the sport’s licensing board, but was told it needed members who are neutral on the issue.

MORE:Program offers financial rewards for cockfighting convictions

Lujan attended a few cockpit board meetings after being confirmed, but said he hasn’t been called to a meeting in months, ever since it became clear cockfighting definitely would be prohibited by federal law.

“We kind of lost interest in it,” he said.

“It’s not going to stop,” Lujan said. “If you’re gonna stop it, then people are gonna do it illegally.”

Mix 102.7 WCPZ Mix 102.7

Mix 102.7 WCPZ Mix 102.7